The market for processed builders’ rubble in South Africa is growing and architects, engineers and the rest of the building industry should take note.

When Dr Kirsten Barnes, waste economy analyst from GreenCape, started investigating a builders’ rubble market, the perception existed that the material was rubbish and that she was wasting her time. This turned out to be way off.

In 2015, 518 000m³ of clean builders’ rubble, was landfilled in the City of Cape Town. In that same year, Barnes estimates that 619 000m³ of clean builders’ rubble was processed and reused based on a survey of six major crushers in the region. She has since come across more crushers in the area.

“This was a very surprising result given the attitudes and perceptions I came across when I first started the project. It means that about 56% of clean builders’ rubble is currently being processed in the City of Cape Town,” she says.

Important to note is that the 518 000m³ in landfill is only clean builders’ rubble, leaving a lot of mixed construction demolition waste loads in drop-offs as well as landfills in the City of Cape Town, and also large amounts of illegally dumped material of which construction demolition waste forms the largest component.

Imagine The Possibility

Local and Dutch experts in construction demolition waste and builders’ rubble processing considered the material coming into landfills in Cape Town, and both independently estimated that 20% to 30% of the material would be suitable for use if streamed correctly, by not being mixed into the stockpile.

“The experts indicated the material would be suitable for sub-base, if not base course, in roads” highlights Barnes. “This translates into 155 000m³ per year available to the market in the City of Cape Town. Looking at a subbase value of roughly R130/m³, that converts to R10 million to R20 million worth of material coming into our landfills per year. Although this rough calculation doesn’t include the processing costs of the material, it gives an indication of the size of the opportunity.

“What’s more, from a national perspective, the Department of Environmental Affairs’ waste baseline report estimates a 3.9 million tons of builders’ rubble was generated, which translates to a value of R44 million to R86 million nationally. When considering that the crushing industry operates on very small profit margins, the processing of materials is not a very costly process and the technology is available.”

Top Applications Of Builders’ Rubble

According to Barnes, builders’ rubble is predominantly used as fill, since a very large performance envelope is allowed, meaning that one doesn’t need a high-quality material. “We further found applications as aggregate in foundations for structures, and where roads and parking lots remain under the authority of the private sector, there is quite an extensive application of builders’ rubble as sub-base and base-course, even for heavy vehicle usage,” she states.

Currently, The Four Main Applications Of Builders’ Rubble Are:

1. Backfill, a relatively low-quality application.

2. Landfill cover, slope stabilisation and building material for landfill roads.

3. Road base and foundation, which is also a popular use for builders’ rubble globally.

4. Re-concreting, where concrete is crushed and re-entered into the readymix or precast concrete processes. Because of the higher quality required, extensive testing is needed, but there is also potential for extensive cost savings. However, since this application is far more sensitive than the others, in secondary materials economies globally, re-concreting is one of the last applications to develop in the market.

A Growing Business

The crushers interviewed further indicated that they had repeat customers, which points to the quality and consistency that they are generating. Many of the top-quality crushers, those who produce a range of products, have strict quality control processes and testing methods in place to supply test results to clients on collection of material. In terms of future plans, four of the six crushers were planning expansion, most of them looking at doubling their capacity in the next two to five years.

Driving The Reuse Of Builders’ Rubble

So what are the drivers of this secondary materials economy, given the growth seen in the City of Cape Town and also currently in Gauteng?

Barnes points out that the increasing cost of virgin materials was cited by a study in 2013 of key construction industry stakeholders within the Western Cape as the primary barrier limiting growth in the construction industry. “With increasing energy costs, this is not going to change,” she says.

“It further relates to building sand, of which we have less than ten years left, and we are also reaching the limits of our ferricrete supply. In terms of other stones and aggregates, the processing and logistic costs are where we are going to see the pinch.

“Also, at the moment landfill fees in South Africa are low, but generally across the country, we are heading into an era where we have less than ten years of landfill airspace left. With builders’ rubble making up about 20% of the composition of landfills and incoming waste, and given the fact that it is generally an inert and useful material, we expect provincial and national legislation to increasingly incentivise the diversion of this type of waste from landfill,” Barnes adds.

“We might very well be looking at landfill bans or even the requirement of an industry waste management plan putting the onus on the construction industry to generate its own strategy for the diversion and reuse of the material that it generates.”

Another factor highlighted by Barnes is that due to the high clay content in many of the Cape quarries, the aggregate is not deemed suitable for structural application and recycled concrete, or aggregates with a high concentration of concrete outperforms the virgin materials.

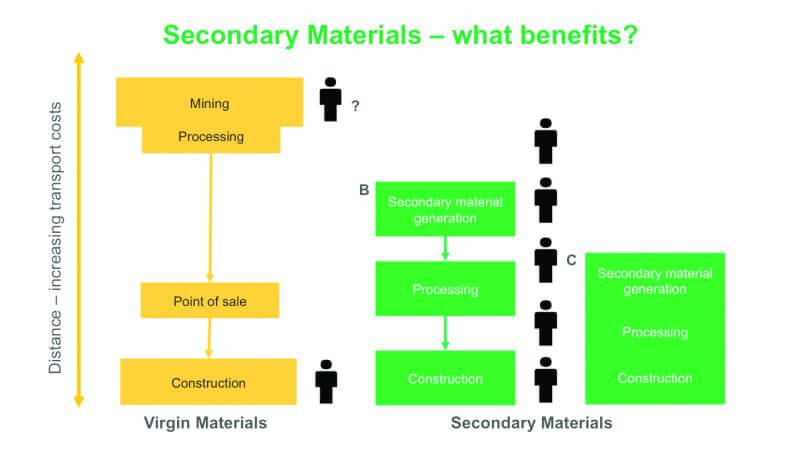

While virgin materials are generally quarried at a distance from the point of sale, with blasting and processing adding costs, sourcing secondary materials collapses the value chain geographically, sometimes even to the same site. International data as well as information from the Western Cape also indicates that for every one person employed in standard construction and demolition, five are employed in secondary material processing. Courtesy of GreenCape.

Many Benefits

• Cost savings

Generally, the extraction of virgin materials happens at quite some distance from the point of sale and point of use, versus secondary material that is often produced much closer, even on the same site, which saves a lot on transport costs.

“Within the City of Cape Town, if we simply divert 60% of the material coming into landfill currently, we’ll see savings in terms of landfill operating costs translate into R224 million a year, which is about 95% of the current solid waste capex budget,” states Barnes.

• Curb illegal dumping

Furthermore, illegal dumping, which costs the City of Cape Town about five times as much to handle as normal waste channels, adds up to about R350 million per year. According to Barnes, these illegal dumping hotspots largely mimic infrastructure gaps, so theoretically, if landfills or crushers are developed in these areas, the available material would be captured.

• Job creation

Also in terms of job creation, which is a key national goal, Barnes’ research findings point to an average of 9,7 jobs per 1 000m³ of builders’ rubble processed. It ranges from 1,2 jobs at crushers that simply produce a fill material, up to 30 jobs at the ones producing a range of different products with a quality control and testing process in place.

“We are talking about jobs at the lowest skill levels, but with a career path. Because of the growth in the industry, the workers have the opportunity to upskill within the industry,” she notes.

• Sensible resource flows

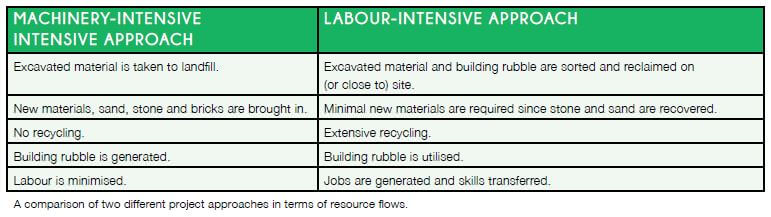

“It is further possible to substitute labour for energy to a certain degree in the secondary materials market. Whereas the primary extraction of materials requires large plants and a limited labour component, in the secondary materials market, there is greater potential to include labour.”

What Is Holding The Industry Back?

Despite the fact that the reuse of builders’ rubble makes logical sense, there are certain concerns causing built environment professionals to be hesitant to step outside the norm.

Mike Aldous, an associate for green building and sustainability services at Mott MacDonald, identifies the legislative lag around standards and a lack of a structured framework of testing and testing methodology that is locally recognised and implemented, as a possible barrier.

“Secondly, the risk component has professional indemnity insurers break out in a cold sweat when you mention that you would like to use recycled aggregate in your structural concrete,” he says. “I think from a waste collection perspective, South Africa still has a very fragmented waste sector which increases the risk element, particularly with asbestos and other contaminants which can slow down the reaction in a concrete matrix.

“We are, however, seeing an uptake of recycled aggregates in mass concrete or low structural risk applications where the performance envelope is more accommodating and failure not life-threatening, cosmetic and utility applications such as kerb stones paving blocks and decorative features show growing uptake as well. But there is still quite a bit of work to be done changing mindsets before it will be commonly used in the primary structure of a building,” he adds.

“Once it is readily available in an ‘off-the-shelf’ kind of way, and successful business cases become more visible to clients, and the track record develops most engineers would be more willing to consider primary structural applications.”

“In an environment of diminishing availability of quality virgin materials, I think we would see a steady growth in the uptake of reused materials, as these resources are depleted the move to fully recycling infrastructure will gain momentum. For the materials supply industry, the key challenge is building trust in these offerings”.

It Is Happening

With a long history of intensive concrete research, Cyril Attwell, director at Arc Innovations, has been involved in several projects where recycled concrete or other waste products were used in structural applications.

While he was working at Murray & Roberts, the concrete designed for the upgrade of the Transnet container terminal in City Deep consisted of 100% recycled G5 material with 70% fly-ash for approximately 99% of the concrete and 50m³ of concrete with zero Portland cement for durability and strength testing. For the Portside project, Cape Town’s tallest skyscraper, up to 85% Portland cement was replaced with waste products. Also on the Gautrain project, 32% fly-ash was introduced, which resulted in significant savings. The concrete used in the Loeriesfontein wind farm project had 10 to 35kg Portland cement per cube, rather than 350kg with waste material replacing on average between 89% and 95% of Portland cement.

“On every one of these projects over the last ten years, we have made sure of the integrity of the data. On the Gautrain project, two different independent South African National Accreditation System (SANAS) accredited laboratories did all the compressive and flexural testing. On the Portside project, Lafarge and the University of Cape Town did all the testing.”

Attwell explains that the amount of testing on these types of concrete is probably four to five times more intense than on normal concrete, because one has to make sure the integrity of the material and data is beyond reproach.

“At the end of the day, it is very well possible – these projects speak for themselves. Each of us just needs to take the next step, put in the effort and be the change,” he concludes.

Full thanks and acknowledgement are given to GreenCape, Mott MacDonald, Arc Innovations and the Green Building Council South Africa (GBCSA) for the information provided.

Rethinking Resource Flows

Donné Atkinson, education and training manager at the Green Building Council South Africa (GBCSA), emphasises the rethinking of traditional construction material flows and the importance of understanding what goes into the products that are specified for buildings.

“Every single material goes through a whole series of processes and along each of these steps, raw materials, energy, water and human resources are used and there is environmental damage. And then at the end of life, it all ends up being dumped somewhere – it doesn’t go away,” she explains.

To minimise the environmental impact of buildings, Atkinson suggests three courses of action:

1. Start changing how you think about waste and start seeing it as a resource. Avoid shipping in materials when it is available locally, either in landfill or from buildings being demolished.

2. Dematerialise designs. Think how you can use less material for the same outcome and design for disassembly so that a structure can be taken apart at the end of its life, making it easier to reuse materials or components or for recycling.

3. Consider the whole lifecycle of the product and make good decisions about what products you specify by understanding what happens to them post demolition or post their useful life.

“There is huge opportunity for professionals in the built environment to minimise the impact of buildings on the environment. The decisions that we make about the materials we choose impact on energy and water as well as our physical environment,” she states.

Caption Main Image: Cape Brick uses approximately 70 000 tons of recycled material per year in the manufacturing of concrete masonry units.

Source: Building and Decor